I’ll never forget the time I got pulled over for a broken taillight.

It was late, and I was coming back to Tuscaloosa from Mississippi, where I had shot pictures at a sorority formal. The night had not been fun. I had gotten lost on my way to the shoot; as it was the early aughts, I’d had only printed Mapquest directions to guide me as I drove my 1993 Ford Ranger to Starkville for the first time in the dark.

Once I got there, a drunk frat boy followed me around all night, calling me a “bitch” the entire time, which he and his friends thought was the height of comedy. I couldn’t wait to leave, but had to wait on another photographer to bring me the film she’d shot at a different event so that I could bring it back to Tuscaloosa.

After the other photographer finally showed up, I then had to figure out how to get the hell out of Starkville since my map was no good. I found a gas station and bought a Mississippi road map, which I kept in my glove compartment for at least as long as I kept that truck. I rejoiced as I somehow found myself back on Highway 82, and I heeded my boss’s advice not to speed as I passed through Pickens County.

It was a surprise, then, when I saw blue lights flashing behind me in Gordo. As I pulled over, my eyes started to well up. I forced back my tears as the police officer, an older white man, asked me if I knew that my taillight was out. I told him I did not. When he asked for my license, I remembered at that exact moment that I had left it in the pocket of the denim skirt I’d worn the night before. When he asked for my insurance, I realized that the card I had with me was expired.

All of the frustration from the night hit me at once, and I started sobbing.

“It’s not you, it’s me,” I remember saying to the police officer, as if I had just broken up with him. “I’ve just had a really horrible night.”

The officer was kind. He reassured me that I just had to have my local police confirm that my taillight was fixed and that I had insurance and that I wouldn’t have to pay anything. He even asked if I was okay before sending me on my way.

In spite of my equipment failure, my lack of proper documentation, and my obvious emotional distress, I was never asked to get out of the car. In fact, in all of the times I’ve been pulled over for minor traffic infractions—thanks, Mom, for the lead foot gene—a police officer has never asked me to get out of the car. Not once.

When I finally got back to Tuscaloosa that night, I was exhausted, but I made it home.

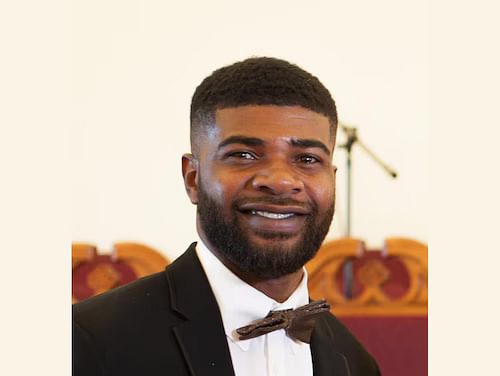

On the morning of August 20, in Bay Minette, Alabama, the younger brother of one of my high school classmates was pulled over for a broken taillight. Somehow, as a result of the sequence of events that followed, OJ French did not make it home.

This incident has left his family and the community looking for answers, not to mention justice. The police department’s version of the story is at odds with many people’s experiences, including my own. Why would a taillight be an issue in the late morning? Why would he be asked to get out of the car for a broken taillight? How did an equipment violation escalate to the point of violence?

How would my story had been different had I not been a young white woman? Would the officer have been able to empathize with me as much had I not looked like I could have been his daughter? Crying is my involuntary go-to stress reaction, but what if my anger and frustration from the events of that night had manifested in a different way? While I acknowledge that white women’s tears have a sometimes sinister power in our society, I still have a hard time envisioning a situation in which I would not have made it home.

I have a hard time envisioning a situation in which anyone wouldn’t make it home after being pulled over for a minor equipment violation, but OJ French did not make it home.

Police have killed roughly 1,100 people per year since 2013, and about ten percent of those killings were the result of traffic stops. Police are supposed to serve and protect civilians, even those of us who sometimes get pulled over for minor traffic violations.

The official story of what happened in Bay Minette is full of holes. As an English teacher, I require my students to back up their assertions with credible evidence. We call this establishing ethos. The Bay Minette Police Department has not released body cam or dash cam footage, allegedly waiting on the results of an independent investigation. However, the public may never see any footage at all, as the Alabama Supreme Court ruled last year that police departments do not have to release body cam footage to the public or the media. This ruling was the result of a different officer-involved shooting in Baldwin County in 2017.

My field of public education has seen quite a few calls for transparency and accountability in recent years. Laws have been made that call into question the books I teach, the way I teach them, and the ways in which I interact with students and their parents. Yet many of the same people who think certain books and ideas are too dangerous do not wish to hold another taxpayer-funded position to the same level of accountability. We teachers don’t even carry guns—just dangerous concepts, like critical thinking, which can lead to even more dangerous concepts, like questioning systems and authority figures.

My own inclination to question the official story is the result of yet another traffic stop during my college years. I was driving back to my apartment from a late meeting on campus. As I drove my daily route from Campus Drive to Hargrove Road via 12th Avenue, I saw lights flash behind me when I reached 17th Street. The officer claimed that I had rolled through a stop sign at the 12th Street intersection. Then he wrote me a ticket for running a red light.

I could have just complied, paid the ticket, and moved on, but none of that incident sat right with me. I wasn’t even sure I had run a stop sign five blocks before he pulled me over, but I knew without a doubt I hadn’t run a red light where one didn’t exist. I decided to fight it.

When I went to court, the police officer and I were both sworn in. The procedure was that the prosecutor would ask the officer a few questions, then I would have the opportunity to ask questions, and then I’d take the stand. The prosecutor asked the officer what happened, and, on the stand, he described an incident that flat out did not occur. He said that I had run a light as it was turning from yellow to red at the intersection of 12th Avenue and 12th Street. I felt a smug grin creep across my face as I anxiously awaited my turn.

When the judge asked if I had any questions for the police officer, I replied, “Yes, are you aware that there isn’t a light at the intersection of 12th Avenue and 12th Street?” The entire room got silent. I added, “I have pictures.” The judge looked at my prints of the stop sign at the intersection, gently warned me not to roll through stop signs, and dismissed my ticket.

As a broke college kid, I was elated. As an adult who has seen way too many people become hashtags, the whole event takes on a different tone. Every time I hear an official police statement, I can’t help but think of the effortless, well-rehearsed lie that the officer told about me while under oath, the details he added to make it seem believable, and the fact that he was not held in contempt for perjuring himself on the stand.

I have never interacted with the Bay Minette Police Department, but I’ve heard anecdotes about them over-policing the Black community for years. These anecdotes are backed up by statistical evidence that shows that this is a nation-wide problem.

Police officers are supposed to serve and protect, and the Fourth Amendment protects us from arbitrary and unfair policing tactics. It is our right and our responsibility to hold police accountable. No one is above the law, not even the people who are charged with upholding the law.

I hope the Bay Minette Police Department chooses the path of transparency in order to gain back the trust of the people they are charged to protect. If the truth is on their side, then they have nothing to hide.

I also hope the French family finds answers. It’s their right to ask questions and seek justice, not only for OJ, but for all of the other folks who got pulled over for minor infractions and didn’t get to go home.